A pleasant walk in Masuda with Dr. Yamamura

Surviving down through the ages together with its rivers – A visit to historical sites of medieval Masuda, which is still alive today Masuda, a city that exudes a medieval atmosphere transcending time

The city of Masuda is situated on the western end of Shimane Prefecture, and has two main rivers: the Takatsu and the Masuda. With their headwaters in the Chugoku Mountains, these rivers flow through the city before emptying into the Sea of Japan, which has a lovely coastline. The Masuda Plain spreads out in the downstream area, in the shape of a delta.

Masuda has a history of considerable advancement by making full use of its geography and topography in the medieval period.

The city still contains many sites from the medieval age, and excavations and research are continuing even today. In light of this situation, Masuda was certified as a Japan Heritage site under the title “Enjoy Masuda, a city that flourished in Medieval Japan – Masuda glows with the brightness of the Age of Regional Revitalization” in June 2020. This is being accompanied by a new appreciation of the historical resources of the Masuda area, and upsurge of attraction to and interest in spots related to its history.

Here, I shall introduce historical sites in Masuda as a crossroads of the medieval and contemporary ages, which I visited together with Dr. Aki Yamamura, Professor of Kyoto University Graduate School who provided commentary, and Kenichi Nakatsuka from the Masuda Municipal History and Culture Research Center.

Let’s take a historical journey to medieval Masuda with Dr. Yamamura, who has a profound scholarship in Masuda’s geography and history.

The age when Masuda shined through use of its terrain

Masuda has a distinctive terrain born of its rich assortment of mountainous, rivers, and sea zones. Life and economic activities there have made the most of this terrain. Masuda took shape while benefiting from the waters of the Takatsu River, which is said to be the clearest in water quality in all Japan, and the Masuda River in various aspects, including food, the environment, sake-brewing, crop cultivation, river recreation, and relaxation.

To begin with, just what age of Japanese history is called “medieval”?

The medieval age lies between the ancient age and the early modern age. More specifically, it covers the span of approximately 400 years occupied by the Kamakura, Muromachi, and Azuchi-Momoyama periods. Generally speaking, it is the age immediately preceding the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate, when Edo was the political center of Japan, and the formation of clans in all parts of the country. It ends around the time of the Battle of Sekigahara.

Medieval Masuda had terrain that differed from that of the present. The Takatsu River flowed into the Masuda River, and the area around the mouth was like a lagoon. This lagoon served as a fine natural port and hub of trade. In addition, the Chugoku Mountains in the upstream areas produced a wealth of resources through their forests, mines, etc. By linking the interior districts and the river mouth districts, the rivers made it possible to export local natural resources.

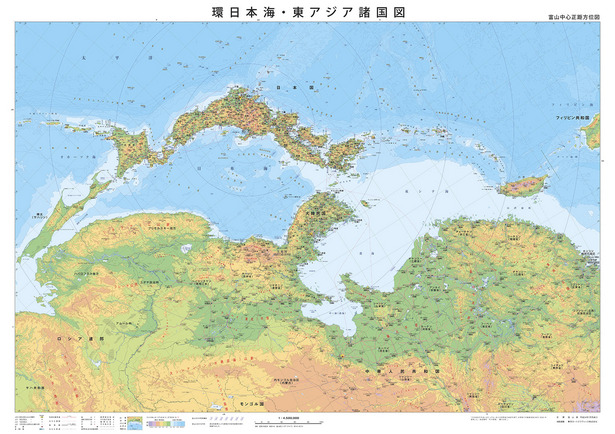

In addition, Masuda lies a relatively short distance from the Eurasian continent, and the Korean Peninsula in particular, across the Sea of Japan. This becomes clear if you look at its location after turning the map upside down. This geographical situation advantageous for commerce also led Masuda to advancement.

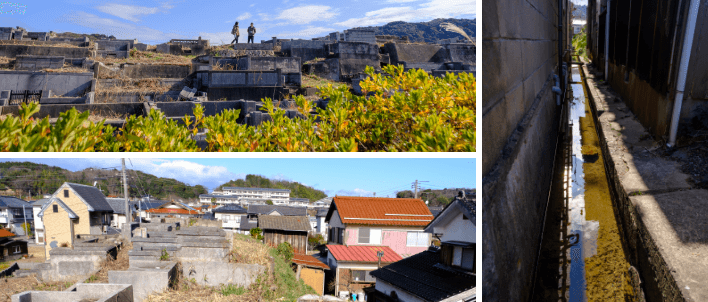

One of the ports along the shore of the lagoon in medieval Masuda is the Imaichi Ruins Site. The site retains stone walls built in the Edo period (1603 – 1868) along the Imaichi River, a tributary of the Masuda River. It is thought that the town of Imaichi was a place enabling maximum use of the boat transport on the lagoon and Imaichi River. Imaichi was also a point for loading cargo brought from the Sea of Japan onto riverboats or transporting it overland. Excavation surveys have found the vestiges of a medieval dock and a landing place in which the river banks were faced with stone. The present town still has little paths that lead down to the riverside.

As noted above, this stone wall dates from the Edo period, but the markets built along the river beginning in the medieval age also were functioning in the Edo period.

One of the old waterways on the Takatsu River was a little river near Kuwabara Sakaba, a sake brewery.

This place is a walk of about five minutes to the Takatsu riverbed at present, but scholars think it used to be part of the Takatsu River, which was wider then.

Kuwabara Sakaba was founded in 1903.

It uses the underflow water of the Takatsu River to make sake reflecting its particularity about the inherent deliciousness and taste of rice. It was designated one of the cultural properties in Masuda’s inscription on the list of Japan Heritage sites, because its sake gives customers a taste of the river’s water.

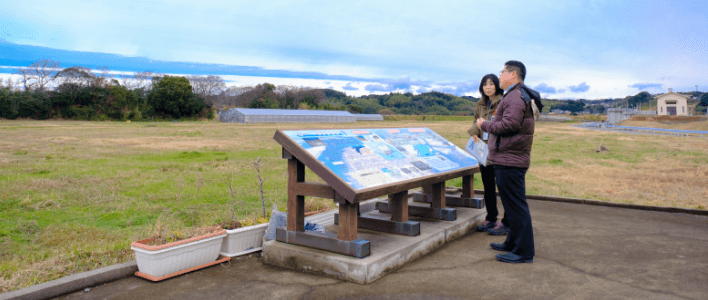

Researchers have also found a place that was used as a port even before Imaichi.

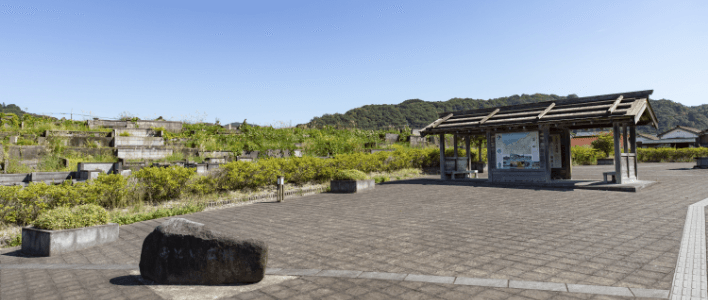

The remains of this port town constitute the Nakazu Higashihara Ruins Site.

It was discovered in the course of a land readjustment project. Excavation of the site yielded remains including a dock lined with pebbles (rocks), a block demarcated with roads, and a smithy. These remains have since been reburied, and a sign on the site provides a description of them. Although called “ports,” the ports of these times did not have piers or breakwaters. The boats landed at the water’s edge and were pulled up onto the shore.

This port was along the shore of the aforementioned lagoon. The terrain acted as bay blocking the strong waves and winds of the Sea of Japan, and created an environment facilitating entry and exit by boats.

The port town had rows of many buildings, and was bustling with people buying and selling goods. Excavations have found fragments of pottery from China and Korea, Southeast Asian countries such as Thailand and Vietnam, and other parts of Japan. This indicates that there was trade with points both inside and outside Japan.

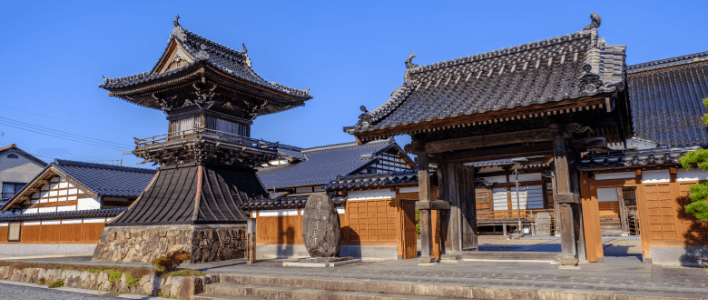

North of the Nakazu Higashihara Ruins Site is Fukuo-ji Temple.

It is thought to have had a deep connection with trade in the medieval age as a temple related to the port.

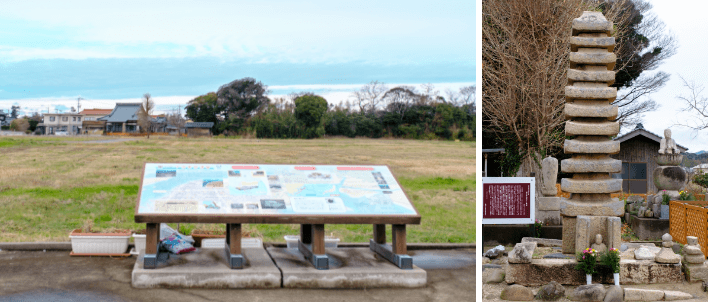

Masuda had five temples whose name contains the character fuku, meaning wealth and good fortune. A stone monument in the shape of a 13-tier pagoda was discovered at the site of the one of them, i.e., the former Anpuku-ji Temple (the current Manpuku-ji Temple). This monument is now on the grounds of Fukuo-ji Temple.

Legend has it that this monument was carried away by a tsunami when it stood on the grounds of Anpuku-ji Temple. Mr. Nakatsuka said the component stones may have been stacked in the wrong order when the monument was rebuilt on the grounds of Fukuo-ji Temple. To be sure, the shape is not a beautiful pyramid that widens toward the bottom. Moreover, it only has 11 tiers now, apparently because not all of the roofs could be found when it was rebuilt.

Other stone monuments, gravestones, and other objects can be found near this 13-tier one. Some of them are reportedly made of Rokko granite from Hyogo Prefecture. If so, this would evidence commerce in the direction of the Kansai region via the Seto Inland Sea. Others are made of Hibiki stone from the medieval province of Wakasa and Fukumitsu stone from the nearby Iwami silver mines, and suggest that there was exchange with various regions over the sea.

When I went around to the cemetery behind the temple, I found sandy ground. In short, there were sand dunes that protected the port of Nakazu from the strong winds blowing off the Sea of Japan. The dunes remain today, and the road leading to historical sites after crossing them in a north-south orientation is thought to date from the medieval age.

The lagoon formed by the river and its flow at its mouth therefore played an important role in the prosperity achieved by Masuda through commerce.

The wood, minerals, and other resources born of the bountiful nature in the Chugoku region were carried down rivers and transported to points in other countries through the port. Likewise, the cargo and culture from trade in the opposite direction were carried from the port via rivers to the city, which flourished as a result. It can be seen that maximum use of rivers was at the core of Masuda’s economic activity.

The Masuda clan – the powerful clan that built and ruled Masuda

As described above, the major reason for the advancement of medieval Masuda was the extensive use of geographical factors. What supported this economic advancement was political power. The Masuda clan, who became the lords of Iwami, the province containing present-day Masuda, brought a stable peace to the city with their excellent political skills, and supported its prosperity based on trade.

Mountaintop castles were built in all parts of Japan in the medieval age, even before the construction of the famed Azuchi Castle by Oda Nobunaga.

Nanao Castle is the main one in Masuda.

When they hear the name “Nanao Castle,” most people think of the castle with the same name in Ishikawa Prefecture. However, the one on Mount Nanao in the city of Masuda was the residence of the Masuda clan, and is an imposing structure that can stand comparison with the one in Ishikawa.

The castle was built over the whole of Mount Nanao. It is a majestic medieval mountaintop castle that has a total length of about 600 meters from one end to the other, and fortified the whole ridge.

According to Dr. Yamamura, one can get more enjoyment out of mountaintop castles by learning about things such as how their construction prepared for defense against attacks and used the terrain, and the reasons for building them at that spot. But first, we have to climb up to the castle.

“Nanao Castle is not too far up, and was easy to use as a castle,” said Dr. Yamamura. The Honmaru (innermost defensive enclosure) was at the location of the Ozaki enclosure in the Northern and Southern Courts period, was gradually moved to higher places.

Even today, the location offers excellent scenery including a panoramic view of the Masuda Plain and the Sea of Japan beyond.

The Nanao Castle site has remains of structures that take the mind back to its past, including earthworks, ditches, foundation stones, and wells.

The Masuda clan was in a relationship of confrontation with the Yoshimi clan in the domain of Tsuwano. Because the Yoshimi had ties with the Mori clan, the Masuda presumably had to take account of the need for protection from the Mori as well, and build a castle with a high defensibility.

The vestiges of a garden have also been discovered in the central part of the castle. I find it highly interesting that the Masuda prepared space in the castle for entertaining guests, holding official ceremonies, etc. This is also evidenced by documents and excavations.

The days when Masuda Fujikane, the 19th head of the clan, lived in Nanao Castle match the age of remains of earthen crockery, unglazed earthenware, and other articles of presumably everyday use found at the site. It is consequently thought that the Masuda family and their retainers were residing in the castle in the second half of the 16th century.

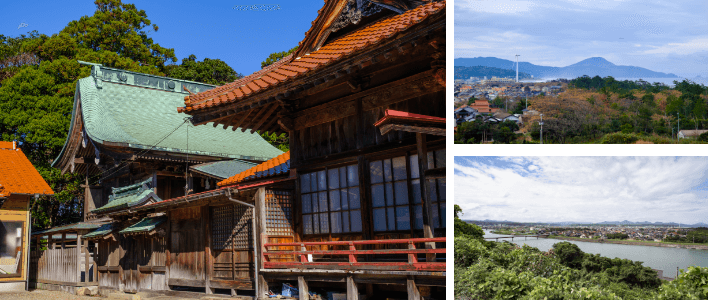

Sumiyoshi-Jinja Shrine sits halfway up the mountain. In the medieval age, it was located in what is now the precincts of Myogi-ji Temple, which I will describe later. In 1658, after Nanao Castle was pulled down, it was moved to the current spot. The present shrine building was reconstructed in 1664.

Visitors can see the big front gate of the castle at Iko-ji Temple in Masuda. The gate is the sole surviving structure from the Nanao Castle of the medieval age.

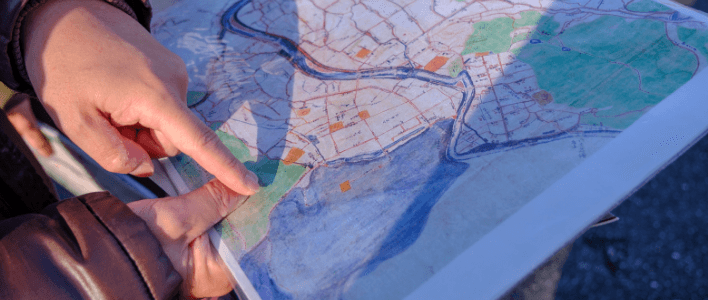

On the other side of the Masuda River from the castle and about 900 meters away to the northwest lies the Miyake Odoi Ruins Site, which was the Masuda clan’s mansion.

Researchers estimate that earthworks were constructed on the periphery of the mansion by raising the ground level, and the river was used as a moat.

The reasons for the selection of this site are its position as a key node of cargo distribution and transportation by riverboat, and the slightly higher elevation of the ground on the island-like site.

Measuring 190 meters east and west, the mansion probably served as the headquarters of the Masuda clan, who came to this spot in order to develop the northern side of the Masuda River. Viewed from the air, the lot is shaped like a boot. Dr. Yamamura said this might be because the construction used the original terrain and river channel as they were.(※)

The earthworks ringing the mansion are as high as five meters. You can get a good sense of how high they are by climbing up to the top.

Behind the earthworks, there is a creek that may have been the remains of a moat.

Although it is not certain when the Miyake Odoi mansion was built, if it was the base for development on the northern side of the Masuda River, its construction may possibly have begun in the first half of the Kamakura period. While Fujikane, the 19th head of the clan, made Nanao Castle his base, it is said that the clan returned to Miyake Odoi in the days of his son, Motoyoshi.

In July 1983, the cities of Hamada and Masuda suffered major damage from flooding due to torrential rains that are still talked about. In the wake of this disaster, a road was constructed through the Miyake Odoi Ruins Site in order to ensure an emergency route for evacuation and rescue. On this occasion, special measures were taken to protect the reliquary structures under the road. At the same time, the city constructed Odoi Square, a park containing restorations of the remains of the well, arbor, and smithies.

The distinctive culture that flowered in Masuda

One subject that cannot be neglected in any discussion of Masuda’s history is the legacy of Toyo Sesshu.

This is also one of the achievements credited to the Masuda clan.

A zen monk active in the Muromachi period (1336 – 1573), Sesshu journeyed to Ming-dynasty China on a ship dispatched by the Ouchi clan. After studying brush-and-ink painting and other arts there, he returned to Japan and built gardens in various places. These are called “Sesshu gardens,” and there are not one but two major ones right here in Masuda.

Sesshu was reportedly invited to Masuda by Kanetaka, who was the 15th head of the Masuda clan and a friend of his. The portrait of Kanetaka made by Sesshu in those days has been designated a national important cultural property by the Japanese government. There is a bronze statue of Kanetaka near Myogi-ji Temple. He is still revered as the lord who sowed the seeds of the culture that took root in Masuda.

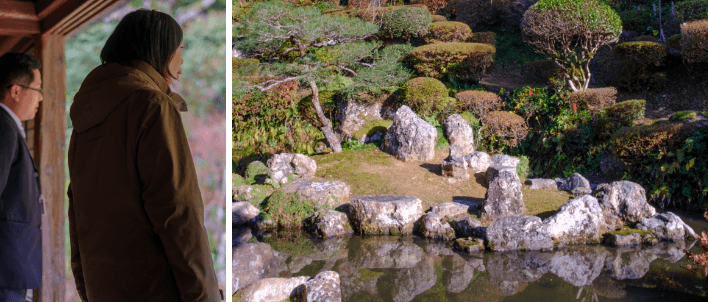

One of the temples that has a garden created by Sesshu is Manpuku-ji Temple.

It is said that Manpuku-ji Temple originally stood near the mouth of the Masuda River and was named Anpuku-ji Temple, but was swept away by a tsunami. Thereafter, Kanemi, the 11th head of the Masuda clan, built the temple here in 1374 and renamed it Manpuku-ji Temple. At this timjie, he also made it the family temple of the Masuda clan.

The main building dates from the time of construction and has been designated a national important cultural property.

The wife of the chief monk of Manpuku-ji Temple told me that the stone garden of the temple expresses Sesshu’s Buddhist sensibilities.

Various stones are positioned in the space stretching from the pond in the foreground to the mound. She said the whole represents Mount Sumeru, which in the China of the day was believed to be an ideal world where the Buddha dwelled.

According to Dr. Yamamura, for the Masuda clan, Manpuku-ji Temple functioned as a facility for receiving guests, and was one of the main spots where they could meet and converse with others while gazing at the garden. It may have been a place that helped leaders of the clan to collect themselves in situations that called for cool-headed decisions in the war-torn times. Sesshu’s garden in Manpuku-ji Temple has been designated a national historical site and a place of scenic beauty. Its appearance still soothes the souls of people today.

The temple still has cultural properties that have been passed down through the ages as its treasures. These include a Niga-Byakudo (Two Rivers, White Road) painting whose composition is said to most closely match the vision of Ippen, the founder of the Ji sect of Buddhism, and a Southern Chinese tri-colored, flower-pattern, five-handled tea urn evidencing the Masuda clan’s trade over southern routes and keen interest in the culture of tea.

Right nearby is a grave that tradition says is Masuda Kanemi’s. This is a must-see too.

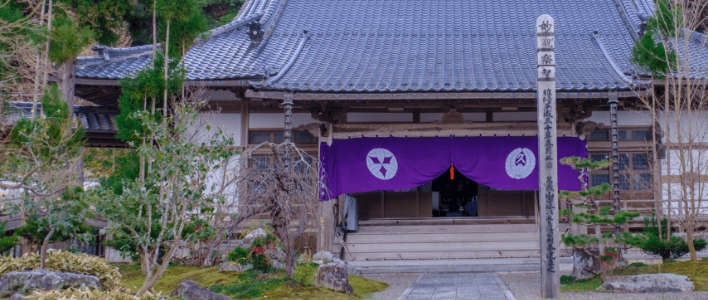

The other Sesshu garden is in Iko-ji Temple. At a site next to this temple on the west, there used to be Sukan-ji Temple, a temple to which Sesshu was invited during the Bunmei era (1469 – 1486).

The garden he built then survives. Sukan-ji Temple went into decline for some reason during the Warring States period, but was revived under the name Iko-ji Temple by Munekane, the 17th head of the Masuda clan.

The garden imparts a sense of the changing seasons for visitors, who come to admire its weeping cherry tree in spring and red maple leaves in autumn.

The placement of stones on slopes creates depth, and the “turtle-island” rock in the middle of “tsuruike”, a pond shaped like a crane, reflects Chinese lore about wizards who live in mountains.

Sojo Yanehara, the temple’s head, recommended viewing the garden from the side as well. It can also be enjoyed from inside the building facing it. People can choose their own way of viewing and appreciating it.

After building these two landscaped gardens I’ve just described, Sesshu journeyed to all parts of Japan and left behind brush-and-ink paintings at various places he visited.

While his doings in his later years are not clear, it is said that he eventually returned to Masuda and died at Toko-ji Temple (the present Taiki-an Hermitage).

A stone monument said to mark the grave of Sesshu lies on a small hill in the precincts of Taikian. Even today, the local residents carefully tend and preserve it.

A city offering encounters with medieval Japan – that’s the appeal of Masuda

Even when taking a casual stroll in its streets, visitors get glimpses of medieval history in Masuda.

On excursions in Masuda, there are still many experiences and spots offering encounters with Japan’s medieval past.

One of the features of Masuda is its large numbers of shrines and temples. The survival of comparatively large and storied shrines and temples is thanks to none other than the Masuda clan, who revived and maintained them in the medieval age.

One example is the Someba Ameno-Iwakatsu-jinja Shrine.

On the grounds of this imposing shrine are a main hall which has been designated a national important cultural property and a building for Kagura dancing whose roof is crowned with a tile bearing the Masuda crest consisting of the character hisa (“long-standing”) between two wisteria flowers.

According to a copy of the ridgepole tag, after the main hall was lost to fire in 1581, it was rebuilt at the initiative of Motoyoshi, the 20th head of the Masuda clan, and under the assistance of his father Fujikane, the 19th head.

Among its attractions are carvings that convey the characteristics of the ornate architecture in the Azuchi-Momoyama period (1573 – 1603).

Another is Myogi-ji Temple, one of the family temples of the Masuda clan. It was reportedly constructed in the days of Kaneie, the 13th head. It underwent a great revival in the days of Fujikane, the 19th head. He invited a monk from Tainei-ji Temple in the province of Nagato (present-day Yamaguchi Prefecture) to head it, and provided for its prosperity by connecting it with influential temples in other areas.

Fujikane is buried at Myogi-ji Temple; a five-tier stone monument said to mark his grave stands on its grounds. The stone from which this monument was made is reportedly granite from Rokko in Hyogo Prefecture.

Over two meters high, this huge stone monument is the biggest five-tier one in all of Masuda. Nearby is another five-tier stone monument said to be the grave of Kaneie.

On the way from Nanao Castle to Miyake Odoi, I came upon Kyo-on-ji Temple.

At the front of this temple is the intersection of the east-west road between Nanao Castle and Miyake Odoi, and the north-south road leading from Myogi-ji, the family temple of the Masuda clan.

On this site are the remains of a kaimagari, a sharp bend in the road constructed for defense purposes.

In keeping with its character as a medieval castle town in war-torn times, Masuda was built with attention to delaying the advance of enemy troops.

The precincts of Kyo-on-ji Temple were moved back toward the main building for a road improvement project, but the pavement stones on the road show the original location.

The photo shows the view facing the direction of Myogi-ji Temple from the kaimagari site.

This area is now a residential district. On the right (western) side was a row of houses of samurai who were retainers of the Masuda clan. On the left (eastern) side is a place that was once a training ground for horsemanship. This is reflected in the name of one section, which is Inu-no-Baba, meaning “dog horse ground.”

People visiting Masuda can not only see the former site of a horsemanship training ground but also ride a horse wearing medieval-style armor themselves, on the beach.

In Masuda, the food of the medieval age is also being re-created.

Interested citizens are conducting a project to reproduce the feast that Fujikane, the 19th head of the Masuda clan, prepared for the mighty warlord Mori Motonari.

Documents from the Masuda clan contain a record of the menu and ingredients for this feast. They show that the meal was prepared with foodstuffs obtained through trade with various areas as well as fish and shellfish that are specialties of Masuda even today.

I found it interesting that, besides local foodstuffs such as sweetish from the Takatsu River, the ingredients included rare treats such as herring roe and kelp from Hokkaido, which was then called Ezochi and virtually the same as a foreign land.

Migita Honten, a sake brewer in Masuda. Mr. Takashi Migita, its 15th head, also serves as the representative of the Masuda Medieval Cuisine Reproduction Project.

His brewery makes Yozaemon and other brands of sake that reproduce the medieval brews. Using this sake, he also launched into the development of iri-zake (a seasoning before the invention of soy sauce).

When the Masuda clan moved from Masuda to Susa in the province of Nagato, the Castletown went into decline. Lamenting this situation, Migita Yoshimasa Somi held “Somi markets” and played a role in the Masuda’s revitalization.

Yozaemon is made in line with the medieval blend and method, with very little milling of the rice.

Because less water is used during preparation, the finished sake has a sweet and deep flavor. It tastes something like thick mirin, a sweet sake used as seasoning.

At the time, it was very much a luxury item, and was even gifted to the Hamada clan.

Because of the low amount of water used in its preparation, stirring it in the vat was an extremely laborious task.

Marushin Soy Sauce Brewer, a local supplier of soy sauce, made the aforementioned iri-zake by adding dried plums and bonito to Yozaemon.

The Migita family learned how to brew sake in the town of Itami, and chose Masuda as the site of their brewery in light of its clean spring water and rice paddies. Founded in 1602, it is the oldest sake brewery in Shimane Prefecture, and continues to make sake under the Somi brand.

The brewery also offers tours of its facilities. (Reservations are required.)

The last stop on this excursion of mine to historical sites was Kushishirokahime-jinja Shrine.

This is an old shrine whose name even appears in the 10th century Engi Formulary. It was carefully protected by the Masuda clan, who contributed land yielding 12 Koku of rice to it. As it enjoyed the patronage of the Masuda, their crest can be seen in various places on the building.

Some of the materials making up the main hall are from the reconstruction by the Masuda clan in the medieval age.

The shrine precincts afford a panoramic view of the Masuda Plain and the mouths of the Takatsu and Masuda rivers.

From the shrine, you can also see Mount Ko, in the Susa district of the city of Hagi. Boats sailing in the area for trade used this mountain as a landmark. The fine view extends all the way to Mount Aono in the town of Tsuwano.

The shrine, too, sits on a prominent spot visible from the sea, and was probably a landmark itself for sailors.

As we gazed at the beautiful scenery of Masuda, Dr. Yamamura summed up the key points of our tour of historical sites:

Taking a bird’s eye view of medieval Masuda, one very important point is that it was clearly a favorable location with a sea zone, river zone, and mountainous upstream zone.

The Chugoku Mountains were the source of minerals (silver and copper) as well as lumber. Rivers were a topographical requirement for transporting these resources, and supported Masuda’s development.

They linked the mountainous and plain zones, and the town grew up through this linkage.

This was accompanied by the political foundation provided by the existence of the Masuda clan, who promoted the town’s economic and cultural development. Masuda had all of the conditions required for advancement.

The people of medieval Masuda thrived by making the most of its distinctive geography, terrain, and local resources.

Dr. Yamamura also noted that a castle town was not constructed in Masuda in the Edo period, after the Masuda clan left, and that Masuda was subsequently not transformed into a big city. In his view, this was responsible for the shape of present-day Masuda, which has medieval elements blended into its cityscape.

While Masuda did not become one of the castle towns, which were the big cities of the times, in the Edo period, researchers think it retained its impressive appearance and unique terrain as a result.

The questions for us from now on are how to make effective use of these local resources that have been passed on to us, and how to go about preserving and restoring them. It is of primary importance to heighten the interest of the people of Masuda and their awareness of the charms possessed by their hometown, which has a history they can be proud of.

Many activities to these ends are already under way. Japan Heritage certification also prompted support for them.

Going forward, I earnestly hope that these activities will deepen the understanding of and empathy with the cultural properties tied to the Masuda clan and development of the city as a site for historical tourism. I also hope that this, coupled with ongoing excavations and research, will help to ensure the sustainability of the Masuda area.

Aki Yamamura (Professor, Kyoto University)

Ph.D. (Literature)

2001: Awarded a Ph.D. after completing the doctoral program at Kyoto University

2001: Began employment as a teaching assistant at Kyoto University

2003: Began employment as a lecturer and associate professor at Aichi Prefectural University

2015: Began employment as an associate professor at Kyoto University

2019: Began employment as a professor at Kyoto University

〇 Field of special competence and research subjects

Historical geography

Study on the location and configuration of cities in medieval and early modern periods (castle towns and port towns) and restoration of urban space in those periods.

〇 Publications

Chusei toshi no kukan kozo (The spatial structure of medieval cities), Yoshikawa Kobunkan, 2009

〇 Membership in expert conferences related to historical sites on the national, city, town, and village levels

Member of a committee for study of improvement of the cluster of sites associated with the Masuda clan castle historical sites (Board of Education, City of Masuda)

Member of a study group for preservation of medieval castle sites, early modern fortress sites, etc. (Agency for Cultural Affairs)

Expert member of the Council for Cultural Affairs (Subdivision on Cultural Properties) (Agency for Cultural Affairs)

Many others

〇 Appearances on TV etc.

Buratamori NHK TV program episodes on the Atsuta district of Nagoya and on the city of Sakata